ARE WE LEARNING ANYTHING?

"WE'RE NOT LEARNING ANYTHING," went the now-viral critique. This week, we ponder what we're really doing at business school, what we're learning, and how it changes the questions themselves.

It’s September 10th, twelve days before what is likely to be our last First Day of School. In the thick heat of late summer, time itself seems physical, expanding like everything else—but, in the end, is not. The days pass; the only way we can count them is down.

For many, business school is an opportunity to pause and to re-take stock, of one’s career, of one’s life. School, alas, does not actually slow time; but it is a privilege to savor time in this way: in classes dedicated to interrogating one’s values, in circles of friends dedicated to designing one’s life to align with those values, in meditative (and sometimes silly) conversations that wind around Stanford’s many sculpture gardens (and even result in the formation of a certain newsletter).

In these moments, in the cradle of magical thinking that, for better or for worse, is Stanford and the Silicon Valley, our many possible futures spread out before us, each beckoning us with its own particular sheen, each, at least in that instant, apparently limitless.

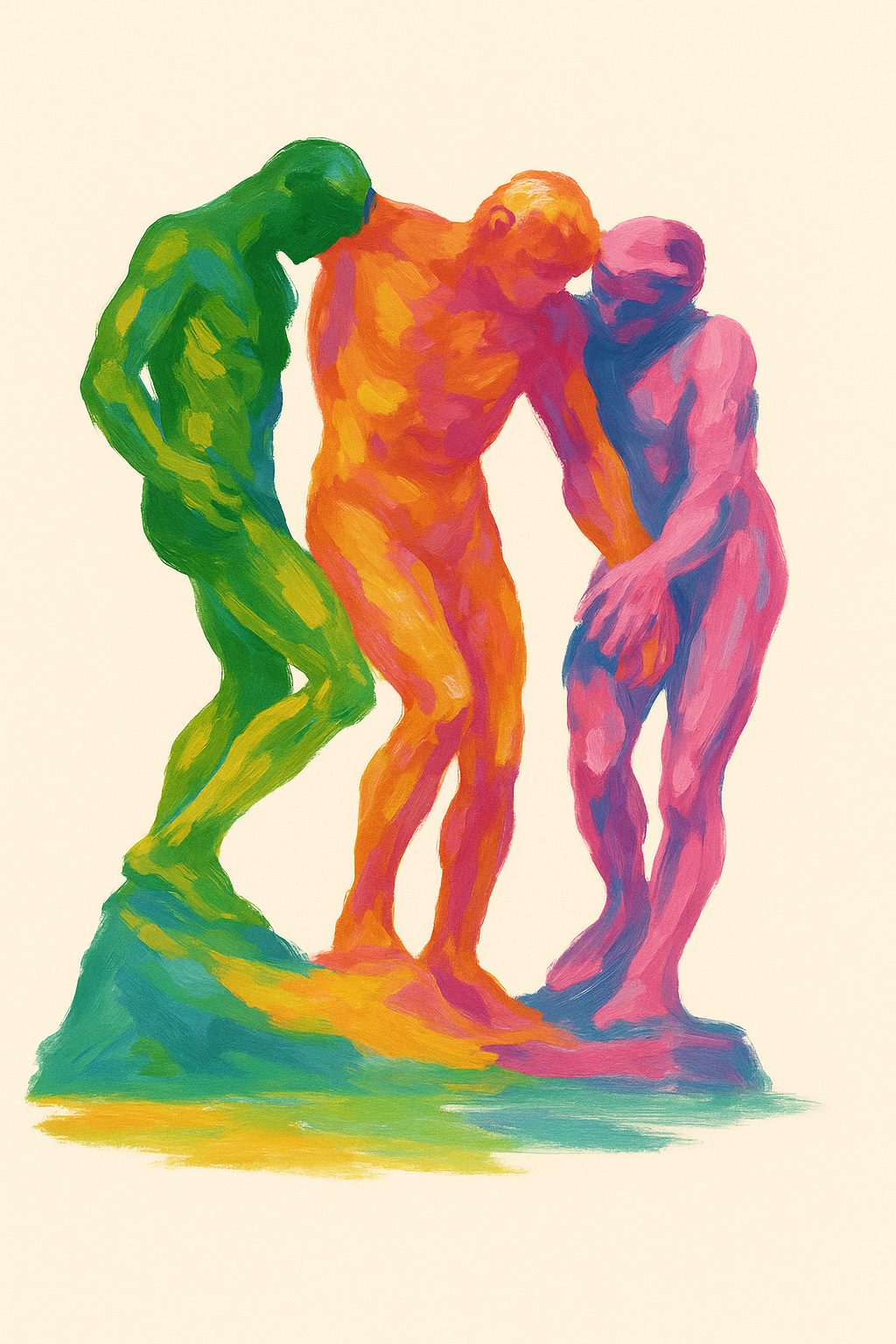

In the Cantor Rodin Sculpture Garden on Stanford’s campus, there is one work in particular that we love: The Three Shades. The three figures are identical casts; their difference is purely one of orientation. So we rotate ourselves into different positions: who we might be if we looked towards building a media company, or raising a VC fund, or founding a startup, or getting a PhD in English, or maybe Psychology, or doing something else entirely.

But the days still pass. Dust gathers on the possible futures not chosen. Rodin’s Three Shades are not alive as we are, but ghosts, perched above his Gates of Hell. Suddenly, we are reminded of the facts: that we can never live out our counterfactual lives, that instead of any of them we have chosen to spend two years in business school, that business school may or may not be preparing us for the actual futures that lie ahead of us, that at some point we will need to begin to answer our questions turned over and over and over and deferred.

The Critique

We think that unease is part of why a recent Poets & Quants article went viral in our LinkedIn circles. Sensationally headlined “WE’RE NOT LEARNING ANYTHING” and cherry-stitched together from student interviews, it punctured the glamour of the GSB, the business school with the lowest admissions rate in the world. With business school ringing in at a cool $170K+, it’s tempting to see the headline as confirmation that the time isn’t worth the cost, perhaps validation for those who abstain. Appetite salivates at the spectacle.

But while Poets & Quants isn’t exactly the paragon of journalistic integrity, the frustrations expressed in the article are familiar and credible: required courses that are frozen in the 2010s, with little connection to an economy transformed by AI despite being set at the source of the sea-change; “Room Temp” cold-call lists that train students to prepare only selectively, when it is their turn; and a lottery system that can leave students unable to take the very classes for which they came to the GSB in the first place. And the anecdotes are reinforced by data: survey scores on classroom engagement have slipped to historic lows.

As much as we might wish to dismiss the click-baity article as just that, the central question it raises is non-trivial: what is the point of business school, if not to learn about how to manage the businesses of today and tomorrow?

After all, professional schools are meant to transmit professional knowledge: lawyers go to law school to learn to practice law; doctors go to medical school to learn to practice medicine. If business students go to business school and…don’t learn to manage the businesses they intend to run or create, then are all of the stereotypes true—that business school is nothing more than a glorified two-year-long break for burned-out white-collar professionals, where all of the hard work takes place before you get in, and from which point you leave with a network-and-brand-inked stamp of approval that grants you undue access to people, capital, and leverage?

For some, there might be truth in that ROI assessment. Over a 40-year-long career, the network and the brand will more than pay back the cost of two years and $170K. Plenty of things have been written about how no recruiter was ever fired for hiring a Stanford MBA graduate. But these answers are tired.

What’s harder to articulate, and maybe more valuable, is the subtler education an MBA can offer: learning how to evaluate and bet on people, including yourself, and how to wrestle with questions that begin with “why.” These are the skills that grow scarcer as everything else gets automated. (Here we must caveat: these arguments are not limited to the MBA, as higher education as a whole is under fire on this front, but that’s another whole can of worms best saved for dinner and a glass of wine.)

A Brief History of the Higher Aims (and their abandonment)

It might surprise you, and then not surprise you at all, that the MBA was born as a reputational project. At the turn of the 20th century, “big business” faced public mistrust after a string of corporate scandals. In an effort to recast managers as rational stewards of capitalism rather than mercenary opportunists, the first schools, starting with Wharton in 1881, set out to rebrand management as an academic discipline on par with law or medicine. From the outset, however, the reality was far less noble: schools struggled with overcrowded classrooms and uninspired teaching, and many students prioritized the promise of lucrative corporate careers over “changing lives, organizations, and the world” (so goes Stanford GSB’s motto)—a familiar tension between higher aims and market logic.

Higher education more broadly had already absorbed the logic of industrialization. Reformers in the early 20th century described schools as factory assembly lines, organized around standardization and efficiency. Similarly, government and foundation money poured into business schools after WWII, pushing schools to mass-produce managers through a mechanized, quantitative curriculum-–the birth of “management science.” With the Cold War and the Space Race, this mandate gained further legitimacy: Sputnik in 1957 spurred a national obsession with math, science, and measurable, repeatable outcomes.

Ironically, the very models meant to legitimize management also made it easier to undermine and control it. Agency theory, in particular, reframed managers not as custodians but rather as self-interested agents to be monitored. And business schools fed consulting and finance pipelines with the very tools that eroded managerial autonomy. In other words, the snake eats its own head in an infinite loop of distrust, self-interest, and distrust again.

All of this history then begs the question: if the higher aims collapsed long ago, what, if anything, does business school still teach that justifies it?

On Judgment

In undergrad, the Core at UChicago required one full year of Humanities and one full year of Social Sciences. I’d sit in the library, jittery on late-night caffeine, staring unseeingly through a glass-domed ceiling as I considered Durkheim. His work embodies the “higher aim” of education: to train our judgment to see the invisible architecture of society. His texts taught me to see how norms and institutions might shape behavior as much as individual choice, and that many “facts” are merely social constructions—it is trust in these “facts,” rather than the “facts” themselves, that stabilizes a system.

Later, on the trading floor, the systems I studied were mathematical rather than social. My work demanded judgment, too, though filtered through “universe rules” of mortgage pricing models. The Job-To-Be-Done was to apply them—under pressure and with incomplete information—to determine where the world might move next.

In hindsight, my path feels like a microcosm of business education’s own drift. Durkheim embodied the early higher aim: cultivating judgment by training students to interrogate systems with no single “right” answer. Trading mirrored the mid-century pivot to “management science,” where judgment was still needed but increasingly mediated by models. As I write, I’m seeing a lesson that was portable across stages: how to make decisions when certainty, or completeness, is impossible. Though the form of education may change, the “why” remains the same: the burden of education was always on me, the student, not only to learn the tools, but also to learn the discernment they require.

The “how-to” skills are the easiest to measure and the fastest to package into a curriculum—which is exactly why professional and vocational schools market the hell out of them. My own Achilles’ heel, according to the job market, was not knowing how to “walk me through a DCF [discounted cash flow].” I never did banking, nor sat through Training the Street, so it was the simplest gap to point at and blame school for not filling. But the more I think about it, the sillier the complaint sounds: a DCF is exactly the kind of thing you can learn on Youtube, or outsource to a model, and it’s relevant to most business jobs only obliquely. The fate of codified skills is replication at scale, until their scarcity premium collapses, and they become commodities.

The real work of business school, then, is not to hand you another “how,” but rather to train the muscle of “why,” the sensitivity to the problems worth solving, and the people worth betting on.

Feynman’s line—“If you think you understand quantum mechanics, you don’t understand quantum mechanics”—is a reminder that at the frontier of knowledge, certainty is an illusion. The hardest questions will always demand judgment in the face of incomplete information.

The Sandbox

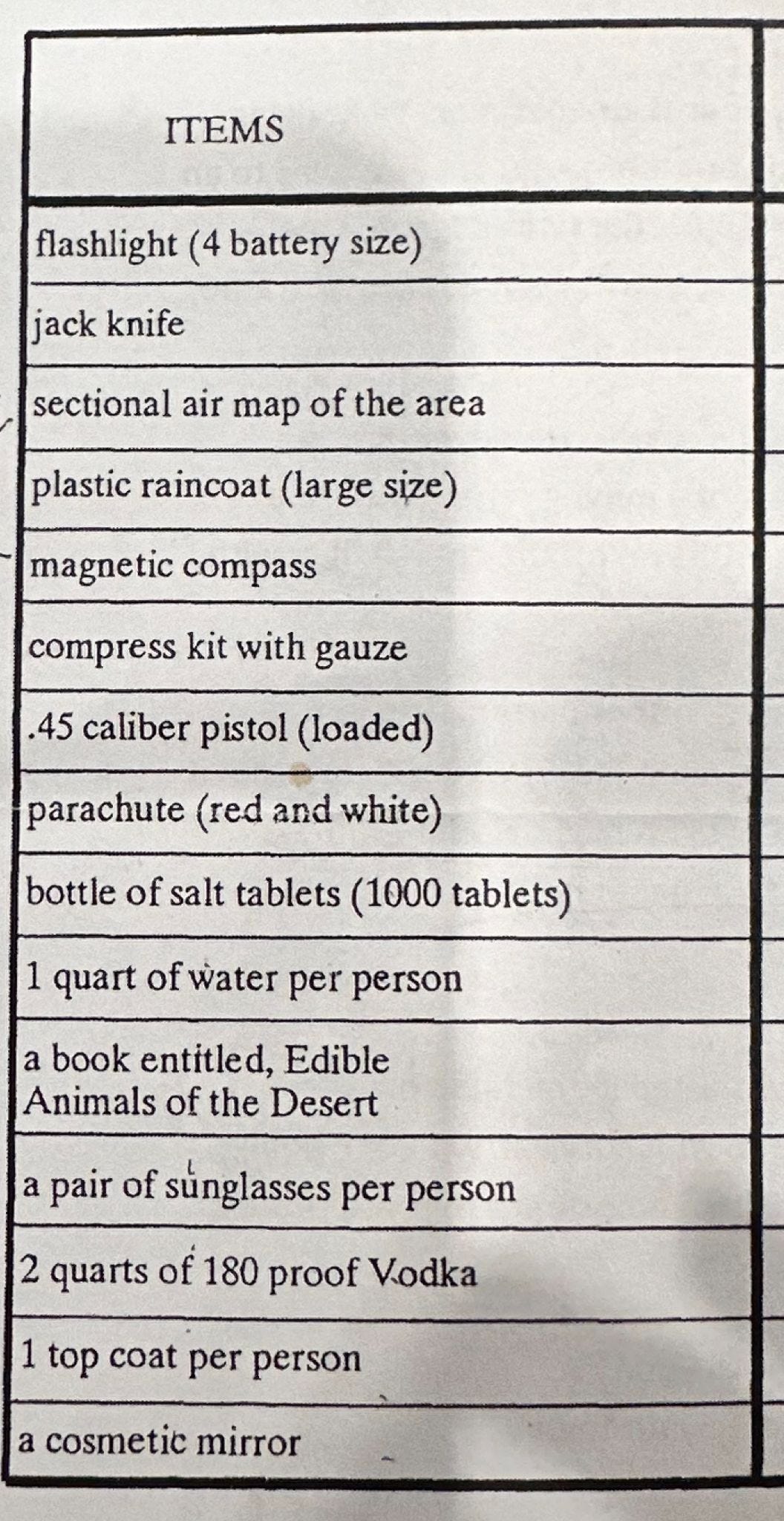

We start the MBA with a class called Lead Labs, designed around a deceptively simple question: Why would anyone follow you? The format is role-play—think fast…a volcanic eruption has stranded your company’s only airport, or: negotiate a term sheet, except—surprise!—the VC hates your co-founder. To anyone with a real job, these exercises probably sound comical. MBAs cosplay crisis management. Even within the class, people split 50/50 between love/hate of the contrivance. When locked in a room to figure out how 6 people survive a fictional plane crash in the Sonoran Desert with 15 random items, the loud athlete might insist on salt tablets being essential, while the quiet engineer might say nothing about the fact that they will absolutely dehydrate you. The group ranks salt tablets first and moves on.

Try it yourself:

Sure, it’s an artificial exercise, but it strips away polish and forces you to notice the rules of power, and how classmates show up under pressure. The MBA is a sandbox where people reveal themselves: in group projects, on trains to Busan, in moments of stress and triumph and pride and existential dread. You learn who follows who, and who follows through. And in learning others, you, still amoeba-shaped and bleary-eyed, begin to learn yourself.

You get to decide what kind of leader you want to be when you grow up.

The point is not necessarily that your future co-founder is sitting next to you in Accounting. It’s that two years of high-frequency exposure whets your senses so that when the right person comes along, potentially five or ten years later, you’ll know. Take dating: most relationships don’t end in marriage, but the full-time DJ you met at Nowadays sharpens your intuition for the kind of person you actually want to spend forever with (I now spend it with only a part-time DJ).

My part-time DJ below:

Statisticians call this kind of search the optimal stopping problem. When faced with a series of unknown options, the math says to spend the first 37% calibrating (reject them all) and then to commit to the next one that beats the best of the first batch. In a parking lot, it means driving past the first third of spaces to set your baseline, then pulling into the next spot that is ideal. Of course life is messier (please don’t run regressions to find the co-founder of your future child). As we’ve said, the model isn’t king; it simply captures something we already do intuitively as we live, make mistakes, and try again. Business school is nothing more, and nothing less, than a dedicated laboratory where one tunes one’s own proprietary judgment model—otherwise known as: wisdom.

Forking paths

I am reminded of Borges’s The Garden of Forking Paths. Every choice to spend time here clears a new field of possibilities. Put more pessimistically, every choice to spend time there closes off countless others. For six years after college, the skeptic in me dismissed business school as wasted narrowing, when the real world is full of paths that at least lead somewhere. That is, until I pulled the trigger three months before the application deadline.

But the narrowing is intentional. You enter the labyrinthine garden now so that later, in the wild, you’ll have an inner compass to guide you. The paradox of business school is that the most valuable thing it teaches is never explicitly taught. What resists direct instruction, and thus what resists automation, is judgment—the “why” behind our insights, our words, and our choices. Why work? Why follow this person? Why this problem, and not that one? Why now? Why me? There is a reason why this is the question that children always ask. Asking “Why?” is how we make it in this world.

Maybe that’s why, despite its credential-factory trappings, the MBA endures. You return again and again to the same question—why did I go to business school?—and discover that the value lies not in its answer, but rather in asking it better the next time. Two years in the sandbox compresses a decade’s worth of natural experimentation, so that when the forking paths appear again, five or ten years later, you recognize the path worth traveling.

That, to us, is the circular book of business school: the end loops back into the beginning, we return to the same questions but as different people, each time with greater sensitivity and attunement. “I could not imagine any other than a cyclic volume, circular. A volume whose last page would be the same as the first and so have the possibility of continuing indefinitely,” says Albert in Borges’ story. Our last First Day of School is no last at all. At least, that’s the idea, if we learn well what business school has to teach us.

Loved this post, beautifully framed! I'd go as far as to argue that this can apply to a lot of professional secondary education programs, where refining your judgement / building wisdom in a sort of "incubator-esque" environment is most vauable though seemingly "intangible" benefit. Thanks for sharing

yes we are learning something new everyday as we have learn to give prompts to ai for maximise growth and reduce working time by using crazy AI prompts for a daily newsletter subscribe promptVault now and have over 500+ prompts pdf and become a prime member and be ahead of most of your colleagues